Eduardo Cardozo was born in Montevideo in 1965. He graduated from the National School of Fine Arts and studied printmaking with Luis Camnitzer in Italy, as well as architecture.

Eduardo Cardozo

Artists

He has held solo exhibitions at Galería Sur, the National Museum of Visual Arts in Montevideo, the Juan Manuel Blanes Museum, Subte Municipal, Artfullliving (Washington DC), Galería Laca (Charlotte, NC), and the Town Hall of Wertingen (Germany). He has participated in the Cuenca Biennial, the Mercosur Biennial, and the "Do ut do" Biennial (Pompeii, Italy). With Galería Sur, he has participated in international fairs such as Arteaméricas in Miami, Cornice Art Fair in Venice, ARCO Fair in Madrid, Arteba in Buenos Aires, and SP Arte in São Paulo.

He has received several awards, including the first prize at the National Visual Arts Salon, the first prize Bicentennial of the National Museum, the Paul Cézanne Award from the French Embassy, and the first prize at the Municipal Salon of Montevideo.

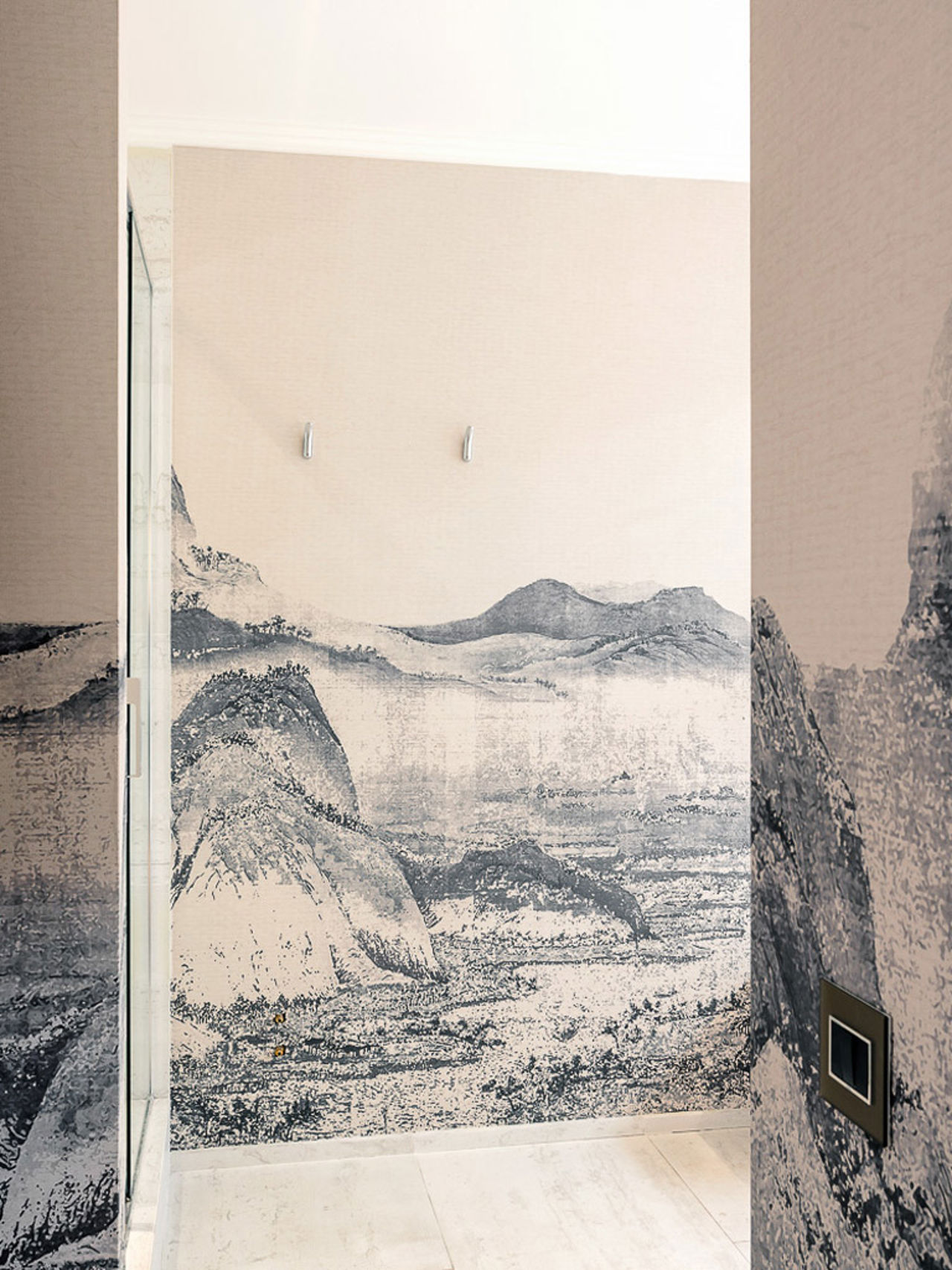

His works are part of important collections in America and Europe. He has completed interventions at Estancia Vik in José Ignacio, "Casa Tierra" at Bahía Vik, murals at Playa Vik, murals in the tasting room and in the barrel room at Viña Vik, and at the Hotel de Chile, as well as interventions at Galleria Vik Milano in Italy.

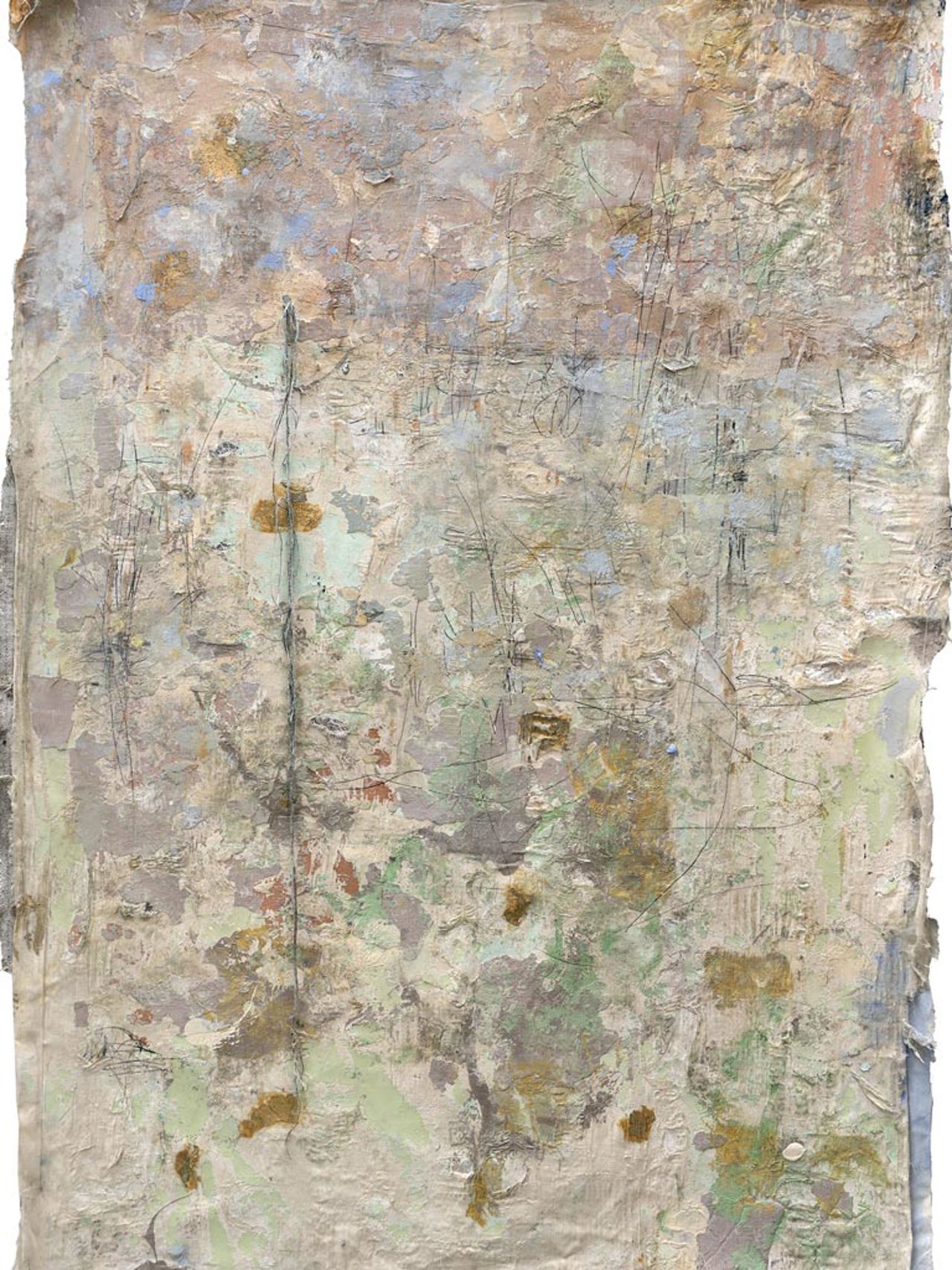

A possible first connection could be made to the sacks of Alberto Burri, created in the late 40s and early 50s. However, the pictorial interventions of the Italian artist were not only miniscule but t he type of burlap used was actually "found": old sacks of coffee and other foods that arrived at the workshop already stained, unstitched, worn , altered by use and time. In short, by "history". In Cardozo's case, the artist is solely responsible for the st ate of these fabrics. The process is thus total: a kind of reconstructive activity by the brushes is added to the long modification work of the medium. Not just mere recovery, but rectification. Layers of colors that at times reconstruct pieces of the ridd led texture, hold it in place where it had given up, make way for calmness – which is also sensorial, aesthetic. Once again with a mainly soothing sky - blue/blueish tone, although other streaks may flourish, including the preciousness of gold (shining in ope n contrast with the degradation of its habitat ), that spill out in opulent healing compositions. In at least on case, Bandera (Flag) – a kind of large, grave anonymous flag, that is nevertheless visually close both to the sky and the Uruguayan flag – , other pieces of fabric appear as patches to fix the tears, mend the gashes, sew the holes. The topic here is accumulation, hybridization, surprise.

These are paintings that at least initially should not be framed. This is because there is a third phase in the ar tist's creation after the preparation/sacrifice of the fabric and the restorative pleasure of painting: the moment it is hang, which allows new – ever - changing – roads. Barely fixed with some nails, the "canvases" show adjustable folds that add to the pain o f the burlap, adding metamorphic perpetuity and movement to the set – almost evoking, due to its continuity, the baroque fold Gilles Deleuze so cherished – while denouncing its weight, which is essentially the weight of color. Likewise, the distance between the fabric and the wall, and the shadows those wounds cast due to the effect of light, grant new depths, creating a sort of ghost - double of the painting. The ramifications of the dismay and the patching multiply.

This kind of obsessive control by the artis t, craftily applied – as far as possible and looking for the impossible – to a production where nothing can be fully controlled, lays the foundation for Cardozo's fusion with his own expressive language. If the new works carefully reveal this symbiosis, then it becomes almost obscenely obvious - but absolutely revealing and attractive - in Basal , a video produced at the same time as the paintings. In it, the scene is filled by his own naked back used as a canvas and it is filmed in hyper - realistic high definiti on that allows to appreciate even the slightest detail, both of the oil paint and the skin. Once again, the medium is problematized, even going as far as to consider himself as a porous (perhaps broken) weave, a wet (perhaps wounded) burlap, ready to recei ve the "writing". In fact, the artist paints himself without seeing, using his body and all of his usual instruments – gouge, paintbrush, trowel, fingers – moving in hortatory fluctuation, through regrets, finishes and new beginnings, clumping and diluting, moving his hands in a rhabdomantic way along his spine, his shoulder blades, his ribs, and distributing – sometimes softly, sometimes roughly – the black, white, sky - blue oil paint, unable to see the result on the spot. This is an emblematic and exemplary mo ment of that continuous challenge of the "next" brushstroke with the unknown, which is the hallmark of his "landscapes". The muscles on his back work so that the arms move and are able to color it: for a few minutes painter and paint seem to blur together.